Kotlin deconstructed: threads and coroutines

Single threading is fun, but if you want go faster you’ll have to go with multiple threads. I already looked at this for Python and found out things aren’t that simple, you can read it here. This time I’ll be taking a look at Kotlin. Kotlin can be seen as an improved version of Java, which is also the case for multithreading. Kotlin introduces something totally new for asynchronous and non-blocking programming: coroutines. In this post I’ll be taking a look at the performance of coroutines in comparison to multithreading and of course the good, old single thread. I won’t be diving into the inner working of coroutines, this might be something for next time. The full source code can be found here. Ready, set, go!

Principles of multithreading

There’s a lot of theory to tell about multithreading on the internet, so I won’t go into a lot of detail here (and the code is also more interesting anyway). In short a CPU core can only do a single thing at a time. So it can only actively run a single process at a point of time. To still be able to run multiple processes (also called programs) at the same time, it quickly switches between the processes. When we run a process, for example a Kotlin program, it will start with a single thread, the main thread. If your program has to do a lot of work or has to do multiple things at the same time, you can spawn new threads. The CPU will quickly switch between the threads of the program, so it can execute all of the at the same time.

So multithreading can be used in two uses case: asynchronous programming to speed up a program and non-blocking programming to be able to do multiple things at the same time. Often if you need a non-blocking program, it’s a hard requirement. If you want to speed up your programming, it’s a scale and not that black and white. Since the last one is more interesting, I’ll be looking at this.

Comparison

To do the comparison some code must be executed to do an comparison on. To avoid any randomness via external factors, like HTTP calls, the code is simple. The work that will be done is a simple increment of a counter. The methods look as follows:

fun work(max: Long): Long {

var counter = 0L

for (i in 1..max) {

counter++

}

if (counter != max) {

println("Counter mismatch")

}

return max

}

fun workShared(max: Long, sharedClass: SharedClass) {

for (i in 1..max) {

// Increment a variable shared between threads

sharedClass.increment()

}

}

// For coroutines a special async function is necessary which contains the suspend keyword

suspend fun workAsync(max: Long): Deferred<Long> = coroutineScope {

async {

var counter = 0L

for (i in 1..max) {

counter++

}

if (counter != max) {

println("Counter mismatch")

}

return@async max

}

}

suspend fun workSharedAsync(max: Long, sharedClass: SharedClass): Deferred<Unit> = coroutineScope {

async {

for (i in 1..max) {

sharedClass.increment()

}

}

}

class SharedClass constructor(var counter: Long = 0L) {

fun increment() {

counter++

}

}

The speed of multithreading depends on how data is handled by the threads. Threads have a shared memory, which sounds nice but it’s also a risk. If thread A and B both write to the same memory (for example a variable), one might overwrite the changes of the other one. The program will behave different than expected and is thus not thread safe. Luckily there are thread safe variables to prevent this, but this comes with a downside. When reading and writing a thread safe variable, checks must be done to make sure no other thread is editing the variable. This can have large impact on the performance, since all the extra checks must be done. Of course there are also other options how data can be shared in a multithreading setup, I looked at the following three:

- Isolated: threads are isolated from each other and don’t share any data

- Returned: all threads do some work isolated from each other and return the result of the work to the main thread

- Shared: the threads will share a single object which will be read and edited as part of the work

One final thing to take into consideration is the amount of CPU cores available. If the program can only use a single a processor, only a single instruction can be executed at a time. If the program can use multiple cores, it can execute as many instructions at the same time as there are cores. To simulate this I run the program in a Docker container and use the --cpus=<value> flag of the docker run command.

Results of isolated

The code for the isolated test looks as follows:

fun isolated(totalWork: Long, concurrent: Int): List<Result> {

val results = mutableListOf<Result>()

val dividedWork = totalWork/concurrent

results.add(time(totalWork, "Isolated-SingleThreaded") { w ->

work(w)

})

results.add(time(dividedWork, "Isolated-Multithreaded") { w ->

val executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(concurrent)

for (i in 1..concurrent) {

val worker = Runnable { work(w) }

executor.submit(worker)

}

executor.shutdown()

while (!executor.isTerminated) {

}

})

results.add(time(dividedWork, "Isolated-Coroutines") { w ->

runBlocking {

val coroutines = mutableListOf<Deferred<Unit>>()

for (i in 1..concurrent) {

val job = async<Unit> {

workAsync(w).await()

}

coroutines.add(job)

}

coroutines.awaitAll()

}

})

return results

}

The time function will return a result object, which contains how long the execution took, the name of the result, the expected work and actual work done. The method that calls the isolated function will save these results. In the repository there is also a simple Python script to visualize the results.

As can be seen the return value is not used. In the multithreading approach a Runnable is used, which is a thread without a result returned aka void. The Kotlin equivalent of void is Unit, so in this case the coroutine doesn’t expect a return value.

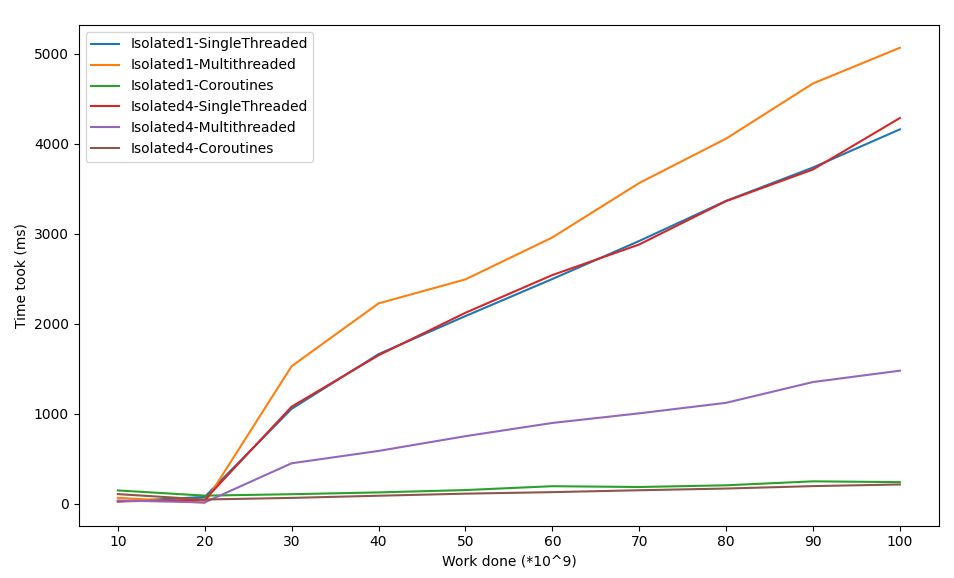

The results looks as follows:

The number after isolated indicates the amount of CPU cores used.

Things to note:

- The coroutines are by far the fastest and more work only slightly increases the duration.

- The different options are close until 30*10^9. I’m not sure what the reason is, but a guess might be that a number doesn’t fit in an Integer (4 bytes) anymore and a more expensive Long (8 bytes) is necessary.

- There’s not a lot of difference for singlethreaded on one or four CPU cores. This is logically, since a single thread only runs on a single CPU cores. When it was run using four CPU’s cores, three cores were idle.

- The multithreaded solution is not too bad when ran on four CPU cores, but when ran on a single CPU core it was actually slower then the singlethreaded solution. The reason is that the single CPU core can only do work for a single thread at a time, so there’s not speed gain due to parallelism. Creating the threads and checking whether they are finished increases the time taken, making it slower than the singlethreaded solution.

Results of returned

The code for the returned test looks as follows:

fun returned(totalWork: Long, concurrent: Int): List<Result> {

val results = mutableListOf<Result>()

val workPerThread = totalWork/concurrent

results.add(timeWithReturn(totalWork, "Returned-SingleThreaded") { w ->

return@timeWithReturn work(w)

})

results.add(timeWithReturn(workPerThread, "Returned-Multithreaded") { w ->

val executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(concurrent)

val works = mutableListOf<Callable<Long>>()

for (i in 1..concurrent) {

val worker = Callable { work(w) }

executor.submit(worker)

works.add(worker)

}

executor.shutdown()

while (!executor.isTerminated) {

}

return@timeWithReturn works.sumOf { it.call() }

})

results.add(timeWithReturn(workPerThread, "Returned-Coroutines") { w ->

runBlocking {

val coroutines = mutableListOf<Deferred<Long>>()

for (i in 1..concurrent) {

val job = async {

return@async workAsync(w).await()

}

coroutines.add(job)

}

return@runBlocking coroutines.awaitAll().sum()

}

})

return results

}

This time the work done is returned, so theoretically the main thread can do do something with it. For multithreading Callable is used instead of Runnable, because Callable can return a value from a thread. The awaitAll method within the coroutine solution returns a list with the results of each coroutine, in this case a list of longs.

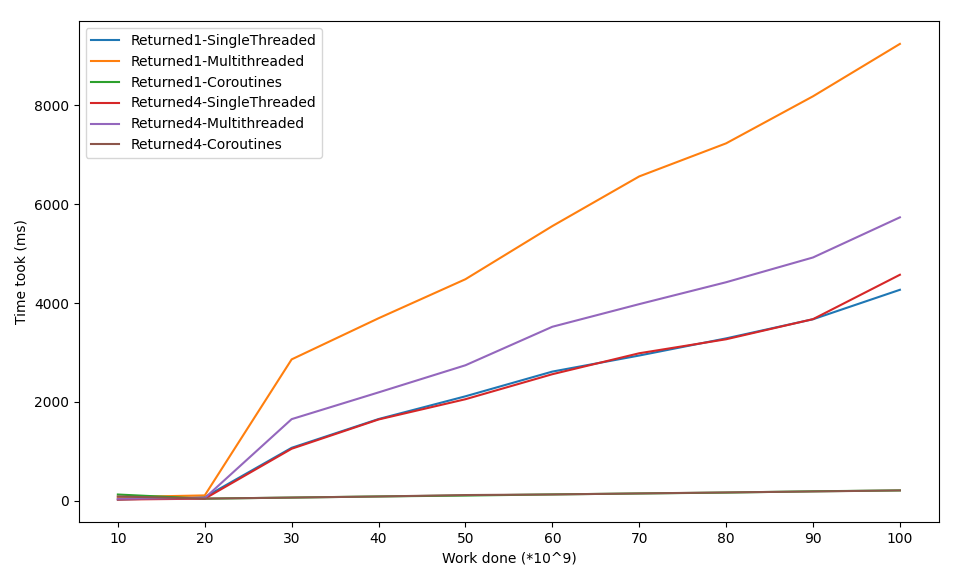

The results looks as follows:

Things to note:

- The coroutines again are fast and there’s no significant increase in the time it took if the work increases

- The singlethreaded approach is actually faster than the multithreaded approach, even if more CPU cores are utilized. I’m not sure of the reason for this, maybe the code could be improved.

Results of shared

The code for the shared test looks as follows:

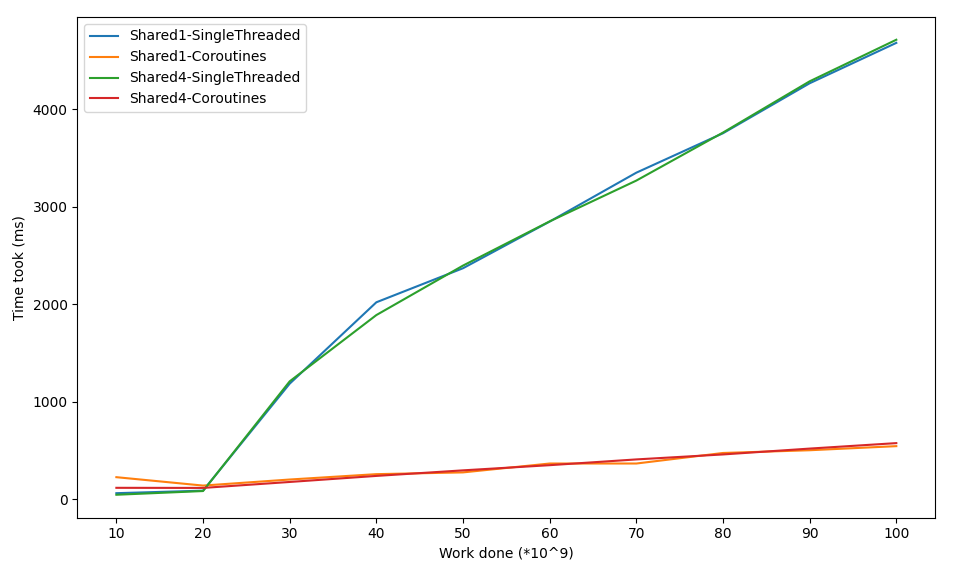

The results looks as follows:

fun shared(totalWork: Long, concurrent: Int): List<Result> {

val results = mutableListOf<Result>()

val workPerThread = totalWork/concurrent

var sharedClass = SharedClass()

val result1 = time(totalWork, "Shared-SingleThreaded") { w ->

workShared(w, sharedClass)

}

result1.totalCount = sharedClass.counter

results.add(result1)

sharedClass = SharedClass()

val result2 = time(workPerThread, "Shared-Multithreaded") { w ->

val executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(concurrent)

for (i in 1..concurrent) {

val worker = Callable { workShared(w, sharedClass) }

executor.submit(worker)

}

executor.shutdown()

while (!executor.isTerminated) {

}

}

result2.totalCount = sharedClass.counter

results.add(result2)

sharedClass = SharedClass()

val result3 = time(workPerThread, "Shared-Coroutines") { w ->

runBlocking {

val coroutines = mutableListOf<Deferred<Unit>>()

for (i in 1..concurrent) {

val job = async {

return@async workSharedAsync(w, sharedClass).await()

}

coroutines.add(job)

}

}

}

result3.totalCount = sharedClass.counter

results.add(result3)

return results

}

The definition of the SharedClass was shown earlier. It’s actually just used as a stable pointer to an object with a number. If an integer was used and passed as parameter to the work function, the actual value would be passed. This if multiple threads would receive it, their initial value of the integer would be the same, but incrementing would just change the value within the scope of the function.

Things to note:

- It shouldn’t by a suprise anymore, but again the coroutines are really fast

- The multithreading measurements are missing, since it wasn’t thread safe. The actual work done didn’t match with the expected work, which means this approach isn’t reliable. What happened is probably as follows: Thread A and B read value of

counter, which is100. Thread A increases the value by 1 and writes back101. Thread B also increases the value it read by 1 and also writes back101, overwriting the increment of thread A. Of course this can be solved by using thevolatile. I tried this by adding the@Volatilekeyword, but the variable still wasn’t thread safe and it increased the duration by a ratio of 100x. This might be something to dive into another time.

Conclusion

Is there a reason not to use coroutines? I haven’t found one yet, except that it makes the code a bit more complex. The performance in all three comparisons was significantly better than the other solutions. Of course in a real program the code might be very different and I can’t say for sure or coroutines are also supreme there. Seeing the big different really draws my interest to find out how coroutines actually work, but this is something for next time.